Earlier this week the vote yes campaign received some amazing news. New polling from Essential Research highlighted a significant enthusiasm gap between yes and no voters. As The Guardian wrote:

Earlier this week the vote yes campaign received some amazing news. New polling from Essential Research highlighted a significant enthusiasm gap between yes and no voters. As The Guardian wrote:

More than one-third of Australians (36%) have already voted, with many more saying they will definitely vote (45%) or probably vote (8%).

Among those who have already voted, 72% voted yes compared with 26% who voted no.

Yes voters also outnumbered no voters in the “will definitely vote” category (57% to 39%) and “will probably vote” (43% to 35%). Among people who say they will not vote, 64% said they did not support same-sex marriage and just 13% said they did.

While of course this is only one poll, it to me replicates the enthusiasm that has been shown in the yes campaign so far. While I don’t agree with all of the tactics of the campaign (check out the latest Queers episode to see why), I am impressed with the huge positive energy, and support from the community, that has arisen so far. And if this poll bears out to be true, it would result in a significant victory.

Despite this positive energy however, over the past few weeks I’ve also seen an alternative trend — a serious dampening of the mood amongst some marriage equality advocates over the potential for success. Recently Rodney Croome and Robin Banks wrote in fear that the movement was stuffing things up, and that the tactics of the yes campaign needed to change significantly. While I agree with some of their criticisms (yes, we do need to tackle homophobia!), their pessimism was quite stark. The comedian and writer Toby Halligan (who I am also friends with) took this even further, preparing us all for the potential of a big no victory — one based in the dodgeiness of the process, as well as the strength of the no campaign and their arguments. Halligan, like many others, pointed to the Brexit and Trump victories as evidence that we should not rest on our laurels — despite there actually being very few similarities between the cases.

I want to be clear before I get started that my intention here is not to psychoanalyse any of the writers I just mentioned, nor anybody else in this campaign. I use these as examples of what I see as a broader mood, one that I think is worth discussing and understanding.

Of course it makes sense to prepare for the potential of a loss. We cannot assume victory, and we must campaign to the bitter end to ensure this victory is secured. Even though I’m optimistic, I will not say defiantly that we will win this vote. We have to make it happen.

But I also want to posit another challenging question: do some of us, subconsciously at least, actually want to lose this vote?

To understand why I’m even asking this question we need to dive into a little bit of theory about queer identity. Bear with me.

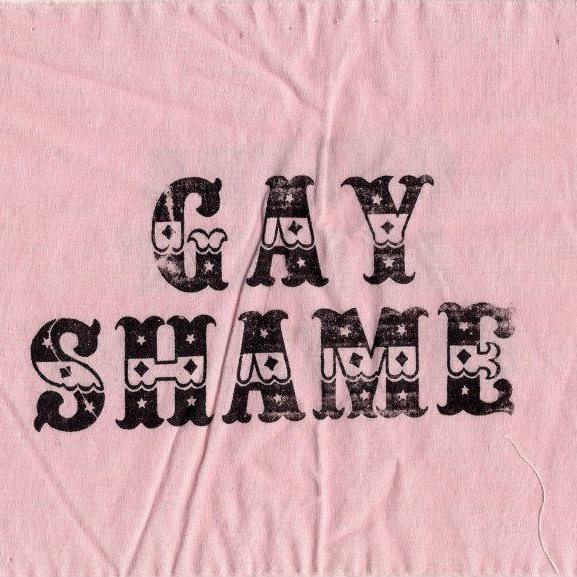

This question is based in a discourse that is prominent within queer communities — one focused around the idea of shame. In her book ‘Feeling Backward’, Heather Love argues that throughout the twentieth century queers have been portrayed as a “backward race”. “Perverse, immature, sterile, and melancholic: even when they provide feats about the future, they somehow also recall the past.” This is a narrative we’re all probably familiar with — queers have been painted as sub-human, a threat to society, and backwards in our approach to sex and love in particular. We are a threat, a threat that is strong enough to require significant intervention — whether that be medical, legal, or social.

The queer theorist Eve Sedgwick expands on this idea, arguing that this framing of backwardness has become so entrenched that shame has become core to queer identity. According to Sedgwick shame forms a foundational part of the queer experience, one which becomes ‘contagious’ within queer communities. She argues that “at least for certain (“queer”) people, shame is simply the first, and remains a permanent, structuring fact of identity.”

The queer theorist Eve Sedgwick expands on this idea, arguing that this framing of backwardness has become so entrenched that shame has become core to queer identity. According to Sedgwick shame forms a foundational part of the queer experience, one which becomes ‘contagious’ within queer communities. She argues that “at least for certain (“queer”) people, shame is simply the first, and remains a permanent, structuring fact of identity.”

Through histories of oppression, queer communities have been framed through the lens of shame and pain. This has often become entrenched within the queer psyche. We have an engrained sense that we should feel shameful about who we are, one that is extraordinarily difficult to escape (check out Benjamin Riley’s great article on this here).

I’m not here to criticise this engrained sense of shame, nor to tell queers to simply ‘snap out of it’. Yet at the same time, I think it is worth thinking about the impacts of the expression of this sense of shame, particularly when it comes to political campaigning. Another favourite of mine, Wendy Brown, argues that, in her terms, this ‘state of injury’ is directed against the general community – the ‘homophobes in the street’ – who are treated as the main perpetrators of the pain directed against us. This, she argues, actually reinforces powerlessness within minority communities. Through seeing the general community as inflictors of pain, injury, and shame we see ourselves inherently through the lens of the vulnerable minority (check out an episode of Queers where Ben and I speak more about this).

This brings us back to the melancholy surrounding the plebiscite.

While, as I said before, I think it is important to be wary about the potential outcome of the plebiscite, and to prepare for an eventual loss, at the same time we have to ask ourselves, is our sense of internalised shame shaping our response? We’ve seen this outcome already, with queers obsessively focusing on, and even actively seeking out, examples of ‘hate speech’ to highlight how bad this campaign is. Every time there is a new flier, poster or ad from the No campaign queers share it far and wide, desperate to show how many homophobes there are out there against us.

There are good reasons to do this — sharing this material makes a point about the extent that homophobia still exists in society. It brings it to the light, which in turn helps us challenge it. I think this is very important.

Yet, given the entrenched nature of shame within the collective queer psyche, it is worth asking, are these behaviours also designed to reinforce that identification? Are we obsessing so much over the homophobia in this debate, at least in part, because we need that homophobia to continue to exist so that we can continue, as Fury argues, “to understand ourselves through the lens of pain”. If pain is so important to shaping the queer experience, then surely we all need to continue suffering in order to be able to define ourselves as queer.

This is why I cannot help but think that a growing collective depressive mood over the potential outcome of this vote may, in part, represent a subconscious desire for this vote to fail. A massive vote for the yes campaign would represent significant challenges to the collective sense of queer identity. It would challenge the idea that there is a majority out there who are against us, and in turn challenge much of the pain narrative that exists in our communities. It opens up the doors for a potentially less-homophobic future, one in which we could challenge our own relationship with shame and suffering. In that sense a potential no vote could be more comforting. It would reinforce how many queers already see ourselves, giving us increased ownership over an identity that is shaped largely by shame and pain.

Of course every queer actually wants to win, or at least they say they would. But a win such as this is also a big challenge — one that could go to the core of our very identity. This is particularly true as a win would come at the hands of the community, and not at the hands of Parliament.

So it’s worth thinking about our relationship to the plebiscite in this way. While of course there is still homophobia in our society, and while of course we must fight against it, are some of the proclamations that this is as bad as it has been for decades really real, or do they represent a relationship to pain and shame that become hard to overcome? I do not know the answer to that question, but I think it is at least one we should be asking.