Part one of a two part essay investigating how sexual and gender oppression are inherent within capitalism.

Originally published in ByLine, 12 August 2015

My thesis is that the history of sexual relations has always been connected with our economic system. More specifically I argue that modern sexual oppression, and how we understand sexual freedom, is inherently linked to capitalism.

So how is this the case, and why is it important? In an essay split over two parts I am going to look at how sexual relations developed via capitalist society, and how this continues to play out today.

In part one I am going to go back in time and look at sexual relations before capitalist society. It is through understanding the history of sexual relations, I argue, that we understand them today.

***

When I first came out as gay at the age of 16 I remember my mum being worried my sexuality would make life more difficult for me. It was a genuine concern, and as a nervous sixteen year old, it was one of the big fears I had as well.

In reality, for me, it has not been the case. Being white, middle class, and from a wealthy city in Australia I’m doing pretty well for myself. I can honestly say that, as far as I’m aware, I’ve never been on the receiving end of any major life-changing discrimination.

This is a sign of great achievement. Of all areas of society, sexual and gender relations have probably seen the greatest shift over the past fifty years. It is easy to forget that at the birth of the second-wave feminist and gay liberation movements in the 60s and 70s women were still largely expected to live their entire lives in the home, while homosexuality remained illegal in most Western countries. Discussion of sex in the public sphere was extremely taboo. Much has certainly changed.

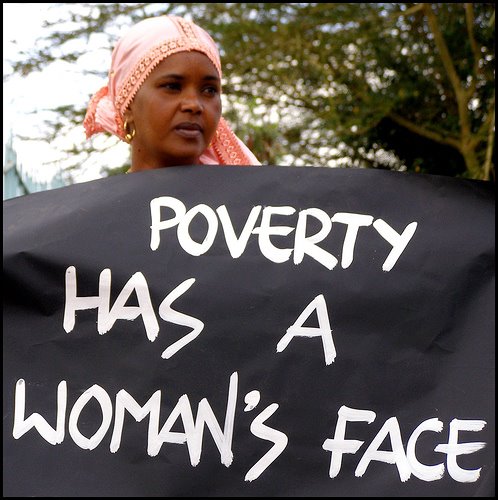

Yet, look a little deeper and at the same time little has changed as well. While gays can increasingly marry, other queers still face significant poverty, discrimination and violence. While some woman are reaching the top of our power structures, the wage gap remains seemingly intractable, violence against women takes lives every day of the week, and restrictions remain on abortion rights in most of the world. The freedoms we have won seem increasingly only available to a few, with the underlying factors of sexual and gender oppression remaining unmoved.

Why is this the case? Is it a matter of us just needing to be patient, or is it because of something much more fundamental? To answer this question we need to look at why sexual oppression occurs in the first place.

There have been many explanations of why sexual and gender oppression exists. Many feminists, for example, argue that male privilege comes down to a biological need for men to dominate, a need they have managed to exploit over different periods of history. For gays and lesbians the answer is often directed at religion and the massive influence it has had on our society.

I argue however that it comes down to something very different — economics.

To understand this we need to look at the most influential sexual institution in our society — the family. From the moment we are born we are all conditioned with values of the nuclear family. We’re told a simple story: you are destined to grow up, meet the boy or girl of your dreams — always of the opposite sex —, fall in love, get married and have children. You will search for this person from the moment you hit puberty and will not give up until you find “the one”.

This is the story of us all entering the modern nuclear family, a relationship that has a range of values imbued in it. The nuclear family allows us to search for one partner and one partner only. That person will remain with us for the rest of our lives, through thick and thin, in sickness and in health. If the relationship ends, as more and more do these days, it is a failure. And of course you will have children, and if you don’t you will be followed around for the rest of your life being asked “when are you going to have children?” or “why didn’t you have children?”

Many see this as the natural way for humans to mate. In fact many scientists have tried to claim that monogamous unions are rooted in our biology. They use evidence such as the supposed ‘low female libido’ or the existence of monogamous unions in one of our close relatives, the gibbon, to back up these claims. The nuclear family, and the patriarchy that comes with it, is as old as society itself.

This story is based in Charles Darwin’s theory of sexual selection. Darwin argued that due to their need to carry and nurture children women have a great investment in their offspring than men. They are therefore much more hesitant to participate in sexual activity, creating a “conflict” between the two genders.

This conflict leads men and women to negotiate what anthropologist Helen Fisher calls the “Sex Contract”. With women producing such “unusually helpless and dependent offspring” they require a mate who can look after both them and their children. Men however are only willing to do this if they can be guaranteed the child is theirs — otherwise they are investing their resources for the genes of another man. In turn men demand fidelity; an assurance their genetic line is being maintained. A contract is formed — resources for fidelity.

In many ways the Sex Contract is exactly how modern relationships have been formed (more on that soon). However, unlike how many of these theorists have suggested it is not actually a ‘natural’ way for humans to get together. Evidence suggests that early hunter gatherer families actually looked very different to this. Many biologists and anthropologists argue early hunter gather societies lived largely in polyamorous relationships where much of the social stratification we see today was non-existent. In fact anthropologists say people in this period practiced “fierce egalitarianism” — that is egalitarianism that is not just a mistake but a thought-out-process. And this was not just for men — women were largely seen to have a high level of authority and power.

That is not to paint a picture of a “nobel savage”. People lived this way primarily as it allowed their communities to survive. Hunter-gather societies existed as small roaming groups where men hunted and women largely gathered. In these societies community was everything — everyone relied on everyone else in order to survive. As Jared Diamond explains, with no ability or need to store or hoard resources, “there can be no kings, no class of social parasites who grow fat on food seized from others”. This was true as well for our sexual relations. As the co-author of Sex at Dawn Christopher Ryan explains, “overlapping, intersecting sexual relationships strengthened group cohesion and could offer a measure of security in an uncertain world.”

So how did the Sex Contract, and the modern family, arise?

The modern family has grown, changed and adapted significantly since our prehistoric origins, but its modern ideals can be found in the birth of agriculture. Hunter gatherer societies did have gender roles — men hunted and women gathered. But this did not mean women had less control. In fact with hunting being a very hit and miss game, women provided the majority of food, and had significant authority and influence in social and family affairs.

Agriculture however changed this. When we began farming humans began to settle down, and in turn start accumulating. With farming we first developed the concept of private property, a notion that changed our society and our sexual relationships dramatically.

Private property did not necessarily change our gender roles, it just changed the value provided to them. Moving from their position as hunters men began to look after the farm, while women largely stayed in the home looking after domestic duties. As resources were now derived solely from the farm, wealth landed in the hands of men. On top of this, as farming required significant increases in labour capacity, women were increasingly forced to stay at home to look after a growing family.

Here we see a major shift in sexual relations. No longer economically independent, and losing much of the community that existed in hunter-gather periods, women became more dependent on men. But men required something in return. Accumulating wealth they now needed someone to pass that wealth on to. In turn men demanded fidelity — the assurance their children were theirs. Here we see the defeat of “mother right” and matrilineal descent. Friedrich Engels described the impact of this:

“The overthrow of mother right was the world historic defeat of the female sex. The man took command in the home also; the woman was degraded and reduced to servitude; she became the slave of his lust and a mere instrument for the production of children. . . . In order to make certain of the wife’s fidelity and therefore the paternity of his children, she is delivered over unconditionally into the power of the husband; if he kills her, he is only exercising his rights.”

Hence we can see how the rise of agriculture and the class society brought much of our sexual oppression with it. Agriculture, and the idea of private property that came with it, led to the development of the patriarchy, and the loss of much of the sexual freedom that existed in hunter-gather societies. It created our first social stratification.

But this is just the beginning. These changes took hundreds of years but were probably some of the most significant in human history. But it is not the entire story we have to tell.

What happens next is what we’ll explore in part two of this essay.

![Image by GedenkstätteBautzen (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://simoncopland.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Einzelfreihöfe.jpg)

![By Jelizawjeta P. (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://simoncopland.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Jelizawjeta_P._Bookshelf_1.jpg)